Charging Foul in Basketball: The Ultimate Rules and Strategy Guide

(Last Updated: February 2026 with current season stats)

Mastering the charging foul isn’t just about knowing a rule—it’s about unlocking a powerful defensive weapon that can shift momentum, erase scoring opportunities, and turn games in your favor. This complete guide breaks down everything you need to know about charging fouls, from the official NBA and NCAA rulebook definitions to the advanced positioning techniques that separate smart defenders from game-changers.

You’ll also get a complete understanding of basketball’s entire foul and violation ecosystem, giving you the strategic knowledge to read the game like a coach. Whether you’re a player aiming to draw more charges, an offensive star learning to avoid them, or a fan who wants to decode every whistle, this is your ultimate playbook.

Part 1: The Charging Foul – Basketball’s Ultimate Defensive Weapon

What is a Charging Foul? The Official Rulebook Definition

A charging foul (defined in the NBA Video Rulebook as a player control foul) is an offensive personal foul called when the player with the ball initiates significant illegal contact with a defender who has established a legal guarding position (LGP).

The Core Rule (NBA, NCAA, FIBA): You, as the offensive player, are responsible for avoiding contact with any defender who has legally established position in your path. If you fail to do so, it results in a turnover—no basket counts, no free throws are awarded—making it a pure defensive stop that swings possession.

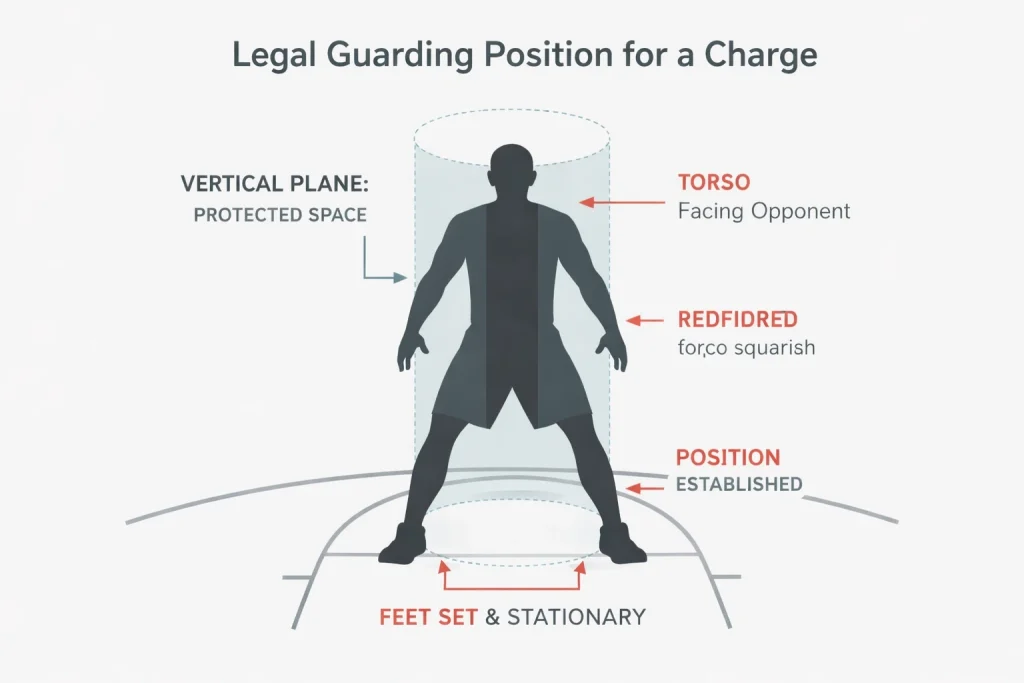

The 3 Non-Negotiable Criteria for a Legal Guarding Position

For a defender to draw a charge, they must meet all three of these requirements before you begin your upward shooting motion:

- Feet Set & On the Floor: Both feet must be firmly planted on the court. The defender cannot be airborne or jumping when contact occurs.

- Torso Facing the Opponent: The defender’s chest must be square to you, the ball-handler. They can’t be turned sideways or facing away.

- Position Established in Path: The defender must be stationed directly in your path to the basket before you initiate contact.

- Myth Debunked: A defender can move laterally or backward to maintain their legal guarding position—they don’t have to be completely stationary. As long as they beat you to the spot and maintain proper positioning, they can adjust their feet.

The Restricted Area: The Critical Exception

The restricted area arc—that 4-foot semi-circle painted under the basket in NBA, WNBA, and NCAA games—is a game-changing rule you need to understand.

The rule: A secondary defender (a help defender, not the primary on-ball defender) cannot draw a charging foul if contact occurs inside this arc.

Why it exists: Offensive players driving at full speed can’t be expected to avoid a defender who slides under the basket at the last second. It protects offensive players and rewards aggressive drives to the rim.

The only exception: If the defender establishes position exceptionally early—well before your gather step—they can draw a charge even inside the restricted area.

Charge vs. Block: The Referee’s Split-Second Decision

This is the most common and controversial judgment call. The difference hinges entirely on the defender’s position at the moment of contact.

| Aspect | Charging Foul | Blocking Foul |

|---|---|---|

| Who Fouls? | Offensive Player | Defensive Player |

| Defender’s Position | LEGAL. Set, squared, and established first. | ILLEGAL. Moving forward, not set, or late to the spot. |

| Point of Contact | Chest-to-chest, defender braced. | Often side/hip contact, defender off-balance. |

| Result | Turnover. Team foul, no points or free throws. | Defensive Foul. Possession stays or free throws. |

The Referee’s Key Question: Did the defender beat the offensive player to the spot?” If yes, it’s a charge. If the defender was still arriving or moving into position, it’s a blocking foul.

How to Draw a Charge: A Step-by-Step Defensive Skill

Taking a charge is a practiced, courageous skill that requires perfect timing and positioning.

Step 1: Anticipate the Drive

Read the offensive player’s movements as the drive develops. Watch their hips and shoulders—they reveal where they’re going.

Step 2: Beat Them to the Spot

Slide laterally outside the restricted area and plant yourself directly in their driving lane before they commit.

Step 3: Get Set & Square Up

Plant both feet shoulder-width apart, bend your knees slightly, and turn your chest directly toward the driver. Your arms should stay within your vertical cylinder.

Step 4: Absorb Contact & Fall Safely

Take the contact on your chest, tuck your chin to protect your head, and fall backward in a controlled manner. Never lean forward or flop dramatically—refs can spot fake charges.

Step 5: Sell the Call Legitimately

A solid, legal collision sells itself. You don’t need theatrics—the impact will be obvious.

Master practitioners to study: Shane Battier, Kyle Lowry, and Marcus Smart built Hall of Fame-caliber careers partly on their high-IQ charge-taking ability.

How to Avoid a Charging Foul: Offensive Counter-Strategy

Elite scorers use skill and court awareness—not just force—to attack the rim without charging.

Euro Step & Side Steps

Change your angle mid-drive to force the defender to re-establish their position. By the time they adjust, you’re past them.

Jump Stop

A controlled, two-footed gather lets you pivot away from set defenders or pass out of trouble.

Shot Fakes & Pump Fakes

Get the defender airborne. Once a defender leaves their feet, they’ve lost their legal guarding position—attack the space they vacated.

Keep Your Head Up

Spatial awareness is everything. See the help defender early and make the smart pass before contact happens.

Part 2: The Complete Basketball Foul System

What Are Personal Fouls in Basketball?

Personal fouls are instances of illegal player contact that impede movement or create an unfair advantage. Accumulated personal fouls lead to disqualification—six fouls in the NBA, five in NCAA play..

Common Defensive Fouls

Blocking Foul

Illegally impeding an offensive player’s path without establishing legal guarding position (contrasted with charging above).

Reach-In Foul

Making illegal contact when attempting to steal the ball, typically hitting the ball-handler’s arm or body.

Illegal Hand Use / Hand-Checking

Using your hands to control, redirect, or impede an opponent’s movement.

Shooting Foul

Making contact with a player in their shooting motion. Results in free throws—two for a regular shot, three for a three-point attempt, or one bonus shot on an “and-1.”

Common Offensive Fouls

Charging

See detailed breakdown above.

Illegal Screen / Moving Screen

Setting a screen while moving, leaning into the defender, or positioning too close to a stationary opponent who doesn’t have time to avoid contact.

Swinging Elbows

Creating unsafe, excessive space with your elbows, whether or not contact occurs.

Flagrant & Technical Fouls: The Serious Infractions

These are the serious infractions that go beyond normal basketball play.

Flagrant Foul 1 (FF1)

Unnecessary contact that’s excessive or not a legitimate basketball play.

Penalty: Two free throws plus possession retained by the fouled team.

Flagrant Foul 2 (FF2)

Unnecessary and excessive contact, often involving violent or dangerous actions.

Penalty: Immediate ejection from the game, plus two free throws and possession.

Technical Foul

Non-contact infractions for unsportsmanlike conduct—arguing with officials, excessive taunting, delay of game, or illegal defensive alignments.

Penalty: One free throw plus possession. Two technical fouls result in automatic ejection.

As of late January 2026, the NBA personal foul landscape features a mix of high-energy defensive specialists and young players still adjusting to the league’s officiating.

NBA Foul Leaders & Discipline Trends (2025-26 Season)

As of late January 2026, NBA personal foul data highlights a combination of aggressive defensive play and learning curves among younger players adapting to official game rules. This highlights how physical intensity and experience differ across teams. According to official 2025-26 NBA season leaders, here is how the discipline leaders currently rank:

Top 5 Players by Total Fouls (2025-2026 season)

| Rank | Player | Team | Total Fouls |

| 1 | Onyeka Okongwu | Atlanta Hawks | 151 |

| 2 | Jaren Jackson Jr. | Memphis Grizzlies | 148 |

| 3 | Wendell Carter Jr. | Orlando Magic | 147 |

| 4 | Karl-Anthony Towns | New York Knicks | 146 |

| 5 | Jaden McDaniels | Minnesota Timberwolves | 144 |

Foul Discipline: Per-Game Leaders

Raw totals can be misleading—they’ll always favor the guys on the floor the longest. The real key is the per-game average. That’s the metric that points to players who are battling foul trouble night in and night out.

- Kyshawn George (WAS): 3.97 fouls/game

- Jaren Jackson Jr. (MEM): 3.77 fouls/game

- Wendell Carter Jr. (ORL): 3.61 fouls/game

Technical Foul “Enforcers”

In the technical foul category, Dillon Brooks (Phoenix Suns) continues to live up to his reputation, currently leading the league with 10 technicals. He is followed by Isaiah Stewart (Detroit Pistons) with 7 and Luka Dončić (LA Lakers) with 6.

Team Discipline

The discipline stats show a real contrast. The Pistons are at the top of the foul list, averaging close to 23 a game—that’s a lot of free points for the other team. Meanwhile, Houston‘s system is clearly working; they’re the league’s best at staying out of foul trouble, sitting at a tidy 18.7.

Part 3: Basketball Violations (Non-Foul Infractions)

Time Violations

Shot Clock Violation

Failure to attempt a field goal within the allotted time—24 seconds in NBA/WNBA, 30 seconds in NCAA men’s, 30 seconds in NCAA women’s.

Backcourt Violation (8-Second/10-Second)

Failure to advance the ball past half-court within 8 seconds (NBA) or 10 seconds (NCAA) after gaining possession.

5-Second Violations

Failure to inbound the ball within 5 seconds, or holding the ball for 5+ seconds while closely guarded (NCAA only).

What Are Floor and Dribbling Violations?

Traveling (Walking)

Illegal movement without dribbling—moving your pivot foot, taking extra steps beyond the two-step gather, or shuffling your feet.

Double Dribble

Stopping your dribble and then starting again, or dribbling with both hands simultaneously.

Carrying / Palming

Placing your hand underneath the ball during a dribble, allowing you to control it illegally.

Backcourt Violation

Bringing the ball back across half-court into your backcourt after your team has already advanced it.

3-Second Violation

Remaining in the painted key/lane for more than 3 consecutive seconds (offensive or defensive, depending on league rules).

What’s the Difference Between Goaltending and Basket Interference?

Goaltending (Defensive)

Touching the ball while it’s on its downward flight toward the rim, or while it’s in the imaginary cylinder above the rim. While charging is a common offensive foul, defensive violations like understanding goaltending rules in the NBA and NCAA also play a critical role in interior defense strategy.

Penalty: Basket is automatically awarded to the offensive team.

Offensive Basket Interference

An offensive player (not the shooter) touches the ball while it’s on the rim, directly above the rim, or within the cylinder.

Penalty: No basket counted, turnover to the defensive team.

Strategic Implications & Game Theory

The Bonus Situation: How Does It Change Defense?

- After your team commits a set number of team fouls in a quarter or half (varies by league), every subsequent non-shooting foul results in free throws for the opponent. This is called “the bonus” or “double bonus.”

- Strategic impact: Once a team reaches the bonus, aggressive defense becomes riskier. Coaches often adjust defensive schemes to avoid cheap fouls that send opponents to the free-throw line.

Intentional Fouling Strategy (“Hack-a-Shaq”)

Deliberately fouling a poor free-throw shooter stops the clock and forces them to earn points from the line rather than allowing easy baskets. This controversial strategy was famously used against Shaquille O’Neal, DeAndre Jordan, and other sub-50% free-throw shooters. Strategic fouling, including the charge-draw, is a primary reason why NBA games actually last over 2 hours in 2026 despite the 48-minute clock

Momentum & Psychology: Why Fouls Matter Beyond the Box Score

A well-timed charge is a massive momentum swing—it energizes your team, deflates the opponent, and can shift the entire complexion of a game. Conversely, a technical foul can derail your team’s focus and give the opponent free points and possession.

Master coaches know: Foul management isn’t just about avoiding disqualification—it’s about controlling game flow, protecting key players, and exploiting opponent weaknesses.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the difference between a charging foul and a blocking foul?

A: A charging foul is an offensive foul where the ball handler initiates contact with a defender who has established a legal guarding position. A blocking foul is a defensive foul where the defender moves into the offensive player’s path illegally or fails to establish position first. The referee’s decision hinges entirely on who “beat them to the spot.”

Q: Can you take a charge without the ball?

A: Yes. An offensive player can be called for a player control foul without the ball, most commonly for an illegal moving screen or by pushing off a defender while cutting. The defender must still be in a legal guarding position for the call.

Q: What is the restricted area rule for charging fouls?

A: The restricted area is the 4-foot arc under the basket. A secondary defender cannot draw a charging foul if contact occurs inside this arc. It is a safety rule to prevent defenders from undercutting airborne drivers. The exception is if the defender is established exceptionally early, before the offensive player begins their shooting motion.

Q: How do you legally draw a charge in basketball?

A: To legally draw a charge:

1) Anticipate the drive,

2) Slide laterally to establish position outside the restricted area,

3) Plant both feet with your chest squared to the offensive player,

4) Absorb contact on your torso before falling safely and controllably.

You must be set before the offensive player leaves their feet.

Q: What happens after a charging foul is called?

A: It results in a turnover (possession goes to the defense). The offensive player is charged with a personal foul, and a team foul is added. However, no free throws are awarded, as it is an offensive violation.

Q: What happens on a double foul?

A: Both players are charged a personal foul, but no team fouls are assessed. If neither team had clear possession, a jump ball/possession arrow decides. No free throws are shot.

Q: What’s the difference between a “charge” and a “player control foul”?

A: They refer to the same violation. “Player control foul” is the official rulebook term for any offensive foul committed by the player in control of the ball or action. “Charge” is the common name for it when it occurs specifically on a drive against a set defender.

Q: Can a defender be moving and still draw a charge?

A: Yes. A common myth is that the defender must be stationary. Once a legal guarding position is established, the defender can move laterally (side-to-side) or backward to maintain it. They cannot move forward into the offensive player’s path.

Q: What is a “no-call” or “incidental contact”?

A: Minimal contact that does not affect the play’s outcome. Referees use the “advantage/disadvantage” principle to maintain game flow.

Q: Who has the most personal fouls in NBA history?

A: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar with 4,657 personal fouls—a testament to his longevity and defensive presence in the paint.

Q: Why is there a restricted area?

A: Primarily for player safety. It prevents defenders from sliding under airborne drivers at the rim, a dangerous play that can lead to severe lower-body injuries like ACL tears or ankle sprains.

Q: What is a “no-call” or “incidental contact”?

A: This refers to minimal, accidental contact that does not affect the play’s outcome. Referees use the “advantage/disadvantage” principle, swallowing the whistle to maintain game flow when no unfair advantage was gained.

Q: Can an offensive player get a flagrant foul?

A: Absolutely. If an offensive player commits a dangerous, unnatural act—like excessively swinging elbows or making unnecessary, violent contact—they can be assessed a flagrant foul (Flagrant 1 or 2), which includes free throws, possession, and potential ejection.

Conclusion: Knowledge is Power on the Court

From the strategic charge to the subtle 3-second violation, basketball’s rules create a complex chess match within the athletic contest. Mastering this guide moves you from a passive observer to an astute analyst of the game, understanding how foul management, strategic violations, and momentum calls often decide championships. Whether you’re a player seeking an edge, a coach designing strategy, or a fan deepening your appreciation, this knowledge is your ultimate playbook.

Mastering the charging foul is about controlling horizontal space, but complete paint defense requires controlling vertical space too. Just as you must understand legal guarding position on the ground, you need to understand legal defensive position in the air. Learn when you can and cannot challenge a shot at the rim with our guide to goaltending rules.

Hello!

I’ve been playing and coaching basketball for over 15 years, and testing gear has always been part of my passion for the game. Over the years I’ve personally assembled and used more than 50 different basketball hoops — from budget portables you can roll onto a driveway to heavy in-ground systems that feel like what you see in gyms.

When I review a hoop, I don’t just copy specs from the box. I set it up, play on it in different conditions, and pay attention to how it holds up — whether it’s rim stability, rebound quality, or how the base handles wind and weather. I also keep up with the latest product releases and feedback from other players so my guides reflect what actually works, not just marketing claims.

My goal here at Outdoor Basketball Shop is simple: to share hands-on, unbiased insights so you can choose the right hoop for your space, your budget, and your style of play. Every recommendation is based on real testing and experience, and I always disclose when links may earn a commission, at no extra cost to you.

. Learn more about me on my about page.